Hamilton: So, I was thinking about things since we last met. We spoke about a number of different things by email, and you had written a couple of pieces that in part contained your reflections on the experience. There were a couple of things that stood out to me. And I know that we had just spoke about this off the recording, but the writing, “Why did this happen to me?” For me, I found it a really challenging and exciting piece of reading because it really strongly pushed back on both deficit and psychoanalytic explanations of delusion because sometimes we only get one or the other that something’s wrong with you or there’s some sort of explanation that at its core is metaphorical even. And you present a third, well, not necessarily third, but a newer perspective. And I’m wondering if you can comment on that a little bit just with regards to rejecting both deficit and psychoanalytic explanations.

Shauna: Yeah, so I posted that on Facebook, and I’ve got a friend with schizophrenia who commented, who really holds to the biomedical model, so takes his illness as being a chemical imbalance. He’s strongly in that camp and I mentioned to him it’s overdetermination where if you’ve got this reductive explanation, do you also need this other explanation? What work is the other explanation doing once you have this physicalist or reductive medical explanation for what is causing something, then to overlay over the top of that something like my explanation, or a spiritual explanation. It’s like that’s doing no work because you don’t need two explanations, one of them will do. But somehow it seems that in my own understanding of what happened to me and the sense I made of it since I was very young (without being so aware or conscious of it) there were two separate causal explanations that I had. And so, you can accept that perhaps this is chemical, perhaps I need medication, and you take your medication. But in making sense of the actual experiences – from a young age I thought that what happened to me…something was revealed when I was psychotic in that I stepped into this alternate world that seemed to be this higher reality that was causally engaging with me. And that seemed real.

And I guess as a young person trying to make sense of that I just accepted that I didn’t accept that there was evil in the universe. In the last interview I said I accepted that these had been ways of testing me and I didn’t know why I was tested or what I was supposed to, that’s why I keep harping on this. What am I meant to have done with my life or did I fail? Or in the last interview saying it sounds hubristic to say you are tested because it’s like why were you special or chosen? I don’t have answers to that. But there was this sense that the beings that I experienced or that were real to me when I was psychotic were somehow good, even though what I went through was often very terrifying, but somehow these beings were good and somehow for some reason they had tested me and I had passed those tests.

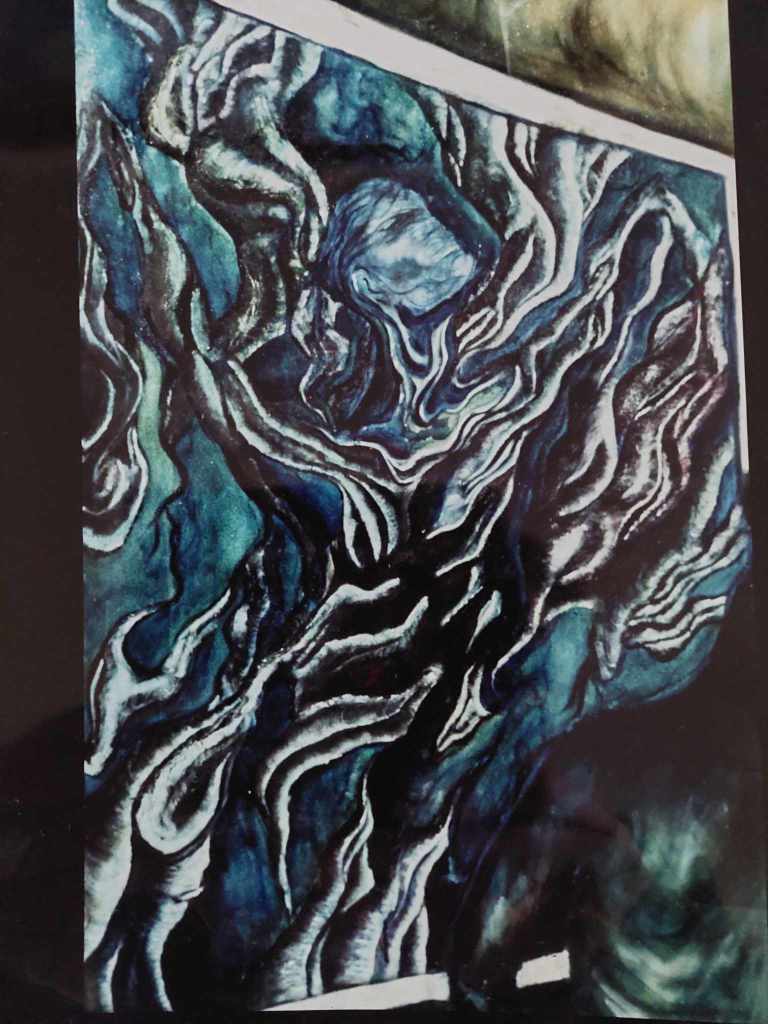

And that’s why I wrote at the end of that piece, it was a bit poetic, but there was this sense that a world was revealed to me. And it feels like a gift to have stepped into that world. And the whole thing does sound delusional to think that you’re tested, and you passed. There’s a lot that I can’t make meaning out of except that the experiences felt real. And I felt that those elders, I called them these higher souls, I felt they were good. They were ancestors, people who had passed on or something, these ancestors, or elders. And that’s how I made sense of my experiences.

And I’m quite a long way away from those experiences now. But doing your research, I want to try and be honest with you. And it’s not something I discuss with people. I mean, my husband jokes about it. I’ve told him, of course, and if a car horn beeps, he says, “oh, what were the elders saying?” But it’s not something I discuss with people because it does sound…if you say these things, what I’ve just said to you, if you say that to people…I know there are all these academics doing delusion research who haven’t had experiences of delusions, and they would look at what I’m telling you and see that as me making meaning out of my experience. So, the experience would still be looked upon as delusional, but it’s like, yes, but you’re making meaning out of it because somehow that helps you in your life. Whereas I’m saying to you that the experience seemed very real to me, and I accept that it reflects some reality even though that reality doesn’t fit into a physicalist framework.

Hamilton: Yes, those researchers from Birmingham and elsewhere from what my analysis is, they cobble on additional features to the currently existing concept of delusion. They say, well, it is true. It is all fine, but also it gives people meaning. But it sounds like you are subverting that all together by, and I also have too as well, which is by presenting this different account altogether, which you’re saying is a part of reality and there is a spiritual component to it. I wanted to ask, when you were talking before about your biology and your chemistry, and there are some sort of Marxist or progressive humanist materialist or physicalist thinkers, and they say, well, of course these ideas are neurological, but they don’t, that obscures social and cultural factors. And that seems to make sense to me. But are you saying that in your experience of a higher consciousness or a different spiritual realm, you are accessing a different part of reality that’s not otherwise accessible to people? That it’s not actually neurobiologically instantiated, it’s accessed in a literal sense?

Shauna: As I’ve said to you, I’ve got these two conflicting pictures of reality and one is a physicalist one where I accept physicalism and in terms of physicalism, it’s not possible to have this non-physical realm. It’s metaphysically not real. But in this other reality I have, yes, I am saying that something happens to the brain and that changes it so that it’s not working in a neurotypical way. But through that, yes, we access something about reality that we don’t normally have access to. The way we access that is going to be influenced by our culture. For an Indigenous person, their experience would be different to someone in a Judeo-Christian tradition and so you’ve got a cultural lens which is going to distort how that reality is going to be experienced by you. And even though I didn’t have a strongly Christian upbringing, mine definitely came through a Christian lens, which is the culture I was embedded in. So, I don’t say that there’s this ultimate reality and that there’s one answer to what that is. We each experience that in different ways depending on developmental and cultural factors about ourselves. But there does seem to be this other reality that we can access when our brain changes in certain ways through chemicals or meditation or starvation or pain. There do seem to be ways that we can modify our experience to bring on these states. Or if we have these illnesses, they happen to us without us doing anything to bring them on.

But yes, so I’m saying yes, there is this state of reality that is different to what we normally access when we’re in the normal waking state with a neurotypical brain. And then I’m saying, yes, there’s something real about that and for me that manifests as these higher souls, higher intelligences or consciousnesses that somehow understand us and, in my reality, have our best interests at heart and causally engage with us in some way. But that’s going to play out differently for people with different sort of belief systems. But again, holding in mind, I am aware of this physicalist picture where none of that…where you can say, well, these beliefs are irrational and they’re not real and they’re not tracking a scientific view of the world.

Hamilton: And that account certainly fits with my own experiences. I’m just not sure then what to do about that, my own experiences of different types of reality. It certainly feels very real, and I know that’s entirely insufficient as an explanation, but it feels very real. So, I’m torn. And one thing that makes me curious about the nature of this kind of other reality is that there seems to be certain themes or concepts that emerge universally, although everyone’s experience is really idiosyncratic, the themes tend to be similar and can involve religion, God, persecution, things of that nature. So, people don’t think that, I’m not sure…maybe there are totally idiosyncratic experiences, but they seem to fall within a certain category.

Shauna: Yeah. This friend I have with schizophrenia who really holds to a biomedical model says that the fact that people often have the very similar delusions – So, when they’re under surveillance by the CIA or whatever – the fact that these delusions seem to have similar themes for him, that really points to it being somehow a biological biomedical thing. But what I was going to say with science, the reason science is so persuasive is that we have these methods that we can use to test things and we make progress from that. So, we have to take the scientific method very seriously and the scientific worldview very seriously. But this was in reference to something you said about science having trouble with understanding these first-person experiences. These experiences are part of humanity and have been in every culture and pointing at the mystics as people who have these first-person experiences or pointing at initiation rites in Indigenous cultures.

And this is something that’s very human – to have these experiences of these altered states – and to give some credibility to them. And it’s really our secular society that doesn’t give credibility to them. And that’s not to say that people with illnesses don’t suffer a lot of distress. I’m not romanticizing psychosis; I’m just saying that access to these experiences has always been there and at times they’ve been taken very seriously to reveal truths about reality. So, it’s another way of accessing insight that is different to the scientific method, but I guess it’s hard to quantify in terms of its truth value, whereas the scientific method gives us this way of testing our claims about the world.

Hamilton: And can do and does a spectacular job of a lot of really fundamentally important things. But I struggle with its ability to account for the gap between what some people’s state is the scientific truth regarding psychosis or delusion and people’s experiences of it, because they’re just disparate. People don’t, unless it claims that that’s a built-in factor or feature of delusions or psychosis, is to see it fundamentally differently from what it actually is. It always feels a bit insufficient for me, especially when I worked in the psych ward. Just like it is not meeting any need. It doesn’t seem to be fitting any plug or connecting with people or having any meaningful potential for impact or anything.

Shauna: It’s a really extreme view of what’s called the explanatory gap in philosophy of mind. So, the idea that we can’t explain phenomenal consciousness or our subjective first-person experiences in terms of why does the brain, which is this physical blob of meat, give rise to first person experience, like our experience of seeing red. And there’s this gap where the physical explanation of the brain can’t explain that experience and what you have with psychosis and the biomedical model is kind of like a really huge explanatory gap. It’s like it really emphasizes what you are saying, well, you have this biomedical dysfunction or whatever that’s giving rise to this psychotic experience. But that first person experience is just so far removed from that reductive explanation. And you’re right then when you come to meet someone who presents at a psych hospital with this huge experience and you give this reductive explanation, it’s not meeting that experience at all. It’s not really explaining the experience for that person or giving the person the sort of support or the container they need to make sense of what’s happened to them.

Hamilton: And just for me, it was for hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of young people that would come in with their life potentially irreparably altered, but it fit for very few people, which is why when I read something like you had written with regards to being tested – for me, it opened a sort of possibility for understanding in a different kind of way than solely the hard science perspective can give for people. And I’m wondering if you could elaborate a little bit on the idea of being tested. Last time you spoke a bit about your own experiences of being tested and it might be useful to refer to them again, but how did you come to know that you were tested? Was that an immediate feeling or did you see others who had the same phenomena or the same felt sense?

Shauna: No, I never spoke to anyone else about it. And as you know, no one asks you about your experience. What I did, I wrote a play about my first experience, I wrote it in 97 and performed it in 98 and 99. And then I made a film about my third experience, which I made in 2000 and 2001. But the experiences themselves were in 91, 93 and 97. And no one really asked me about them, and I don’t recall really explaining them to anyone. So that’s why I made artworks about them at the time because I hoped that someone could explain to me what happened, but no one did. People saw these artworks and I think appreciated them, but no one really sat down and made sense of it for me. And I was also doing it to try to let people know what the experience was like. But certainly, I never knew of anyone else being tested or I never really spoke to anyone. And I don’t know that anyone really picked up on that theme, even though it was in the play.

I’ll say at the time I was in the inner city in Sydney and all my friends would staunchly have been atheists, and I had this God stuff just littered throughout those artworks, but I don’t think anyone even noticed.

Hamilton: Because of the lens that they were coming to it with.

Shauna: I don’t know. It’s this funny thing, you put this artwork out into the world and people I think appreciate it, but whether they don’t know what to say to you – and you can’t badger people for feedback, so you’re just sitting there thinking, “no one’s said anything. No one’s commented or addressed what I put out there”. I put art into the world when I was younger, I’d perform as well, and I’d try to be really honest. And in a sense, I was incredibly lonely at the time. I had friends, but I was quite depressed and really struggling. And I tried to reveal my soul and be honest, and this is a bit off track, sorry, but I’d get very little feedback.

People wouldn’t really address what I was saying and whether it was just too honest, or they didn’t want to take me on as a project because I seemed to…I needed a lot of support and I eventually got that support when I was about 34. I got a couple of older men who were lecturers, and one was an analyst, they’re both psychologists. They gave me a lot of support. But prior to that I needed a lot of support and maybe people could see that, and they didn’t really know how to do that. And that’s why they never approached me when I was putting these works into the world. That’s a bit off topic, but in terms of being tested I spoke to no one, and no one really spoke to me.

Hamilton: And yet that experience was really clear for you or that kind of framing was clear.

Shauna: Yeah, because the episodes themselves were so vivid. They happened a long time ago now, and I don’t dwell on them, but at the time they were so profound, and I remembered everything that happened. And that was a very big theme. As I said to you before, they seemed like very religious experiences. And the first two, I was wandering through the environment from Tasmania to Sydney or from Katoomba on my way to Sydney. And the decisions I made each time I stepped through the environment or every time I made a decision, it was guided by these signs that I was reading, or my thoughts were being heard and sounds in the environment, like I said, were responses to these. So, I had to make decisions based on how I was reading this reality and I had to make the right decisions. And if I didn’t, something like the ground would shake up and down. If I turned the wrong way, the ground would shake up and down and I’d have to turn the other way. So, I am walking through the environment reading these signs and it was important to control my thoughts. Firstly, I had to be humble, so if I had hubristic thoughts, I’d hear this booing in my head and I’d get anxiety. And so, I had to control my thoughts to be humble, even though I thought I’m the Second Coming.

So, the whole psychotic episodes were these stories where the way each decision I made or each thought, I really had to control my thoughts. And I did that for years even when I wasn’t psychotic. If I had a bad thought, I’d squash it down. I was trying so hard to be good and I’d get anxiety or if my thoughts were just, if I let them just stray and then I’d hear a car beep and I knew the elders were good, but they’d be alerting me to what I was thinking. So, I’d have to think what I was thinking and think, oh, I let my thoughts stray. So, I was controlling my thoughts to be good. And the stakes were very high during the psychotic episodes because there was this belief that when I got to the hospital the world was going to be cast into Armageddon and I had to hide who I was from the people around me. And it felt like the experiences were so big and I was so young, and I can’t believe they were a result of my imagination. They seem to have things in them that I didn’t have access to. And it seems as though there were beings that were beyond me who were involved in those experiences because I don’t believe it was just me in those experiences imagining it.

Hamilton: And I know your experience fits really strongly within a tradition or a history of different people being tested in various ways at different times. And to me it seems really epistemically inconsistent to say all people that feel that way are psychotic, but all people in the past that felt that way were religious or spiritual or mystic. My desire for a universal explanation is really strong. But when you think about people of the past, at least with regards to their accounts, do you see a really strong similarity, like an experience?

Shauna: There’s a couple of things there. One is I wasn’t in a container that a mystic in the past living in a monastery is. They are taught, they’re trained very strongly within their discipline or their religion. So, they have this structure for their experience to manifest within. And as a young person, this just came on, I didn’t bring it on, it just happened to me. It was a result of trauma and drug use. I wasn’t within a religious container that could make sense of it. I mean, there are differences. And also, you can say, well, how did someone’s experience result in what they gave back to the world? And I’m not claiming I’m a mystic, I swear I’m not making that parallel at all.

But when, in a paper I quoted in that piece I wrote, they say that these are categorically distinct states. The mystic is not the person with schizophrenia, and they are not the mystic. They’re experiencing categorically different states where one is accessing a non-sensory reality through some kind of intuitive faculty. And the other is having all these cognitive problems and hallucinating and having delusions which are the result of this biochemical dysfunction. It’s like no, both of those experiences are very raw, as I said, experiences of this unveiled reality. That’s how I expressed it. And they are human, deeply human experiences and they hold truths and I believe that. So, I think we’re accessing something that’s very similar. I don’t think they’re categorically different.

But I certainly did spin out of control when I was psychotic. It was very distressing. I did need to be treated to be brought down. It took a long time to recover from. Perhaps my experience would have been different if I had had some other sort of treatment where people could contain me and make sense of my experience. Rather than being this young person just left to pick up the pieces. But the mystics were contained in an environment where they had discipline, and they were learned. They were trained in their particular religion. And so, I don’t say they’re the same, but I don’t think they’re categorically different experiences. I just think one spins out of control because if you’ve got schizophrenia, you don’t have that training, you don’t have that support, you don’t have that container for the experience to be made sense of.

Hamilton: Yeah, that’s very insightful. That makes a lot of sense to me because it might’ve been evident from the question – I was just reflecting on historical people and events and thought that seems similar to some people I know or worked with. And for us to be resigning them to a non-explanation, I know an illness model is an explanation, but it doesn’t really explain very much. I know I’m reaching and sound very biased, but it seems cruel to me. It seems borderline cruel or unfair to not support people to develop a sense of their experience, locate it and reflect on it in a safe and comfortable environment. And when I hear about being tested, I wonder how many people that applies to, because a lot of people have to go through strife, and I guess trials in their experiences of psychosis and delusion. That seems to be a relatively common theme. So, it seems like to be tested is to be human almost, whether it’s in a really profound way or in a more benign manner. Do you think it has any relationship to the being tested that people experience in everyday life? Is that a similar thing or is that not related?

Shauna: We all go through trauma and even if you have great parents and you don’t have developmental stuff, one of your parents is going to die. Both of your parents are going to die, someone is going to get cancer, you’re going to get Alzheimer’s. Even if you have this really supportive, strong upbringing, we all face trauma. But I guess with the psychotic episodes, I think everyone, and I can’t make a blanket statement like that, but I have interviewed 16 people about their experiences. And I think they’re all huge and disturbing experiences. They’re all, I would say they’re all ordeals and tests – whether people would express it that way or not. But I’d say that the point that I get upset about is that there is stigma attached to these experiences and I don’t understand why. And I never did. Long before I started my research, I never understood why people who experienced psychosis were stigmatized because they’re such huge experiences and it’s really hard to come out of them and then pick up the pieces.

And we have different rates of success at pulling our lives together. And a lot of that depends on the sort of supports we get. But a lot of the reasons that people don’t flourish with these illnesses is not because of the illness, it’s because of the stigma in society, the self-stigma, being overmedicated, not having good economic prospects. There are all these reasons that make life really hard for people with these illnesses. And it seems so unfair because I always thought we should be celebrated. I always thought I should be handed a certificate or degree for surviving it and coming out of it…we should be going to a graduation ceremony, not be stigmatized by society. And that’s the cruel thing because they are big experiences.

Hamilton: Many people that I’ve been talking to, in fact, I think five other people have said specifically that the impacts of disclosing their experience to others such as forced treatment, forced medication discrimination, health impacts was universally worse than the distress of the experience that they had to begin with. Which was hugely remarkable for me because I didn’t really…they’re all saying of their own accord that the impact of the experience itself is very hard, but the flow on effects, those were the things that seemed to be really be harmful. And you mentioned before, during your experience, you’re very concerned about being a good person controlling your thoughts in order to be good. This might sound counterintuitive, but was that good? Was that a rewarding experience? Do you think it has had positive impacts on you or was it in fact detrimental in the long term?

Shauna: Yeah, I think I remained quite young. I was 34 when I got support by a couple of good mentors. And I mentioned that one of them, he was an older man and wise. He’s a beautiful man. I’m still in touch with him. He told me to stop being good and stop trying to be special. And I think trying to let go of all of that in a way, I mean, what I’ve done for a long time is focus on my uni work and not really focus on ‘spiritual practice’. Part of my past, I was involved with a Buddhist group, and everyone would say, are you practicing? This idea that, if you practice really hard, you’ll reach Enlightenment. So, how’s your practice going? So, the idea is that you need to be practicing.

And I think I had to loosen that up and I made conscious decisions and I chipped away at my uni work very slowly. I found it very difficult. So, it’s taken me a long time to reach the point that I’m at. But that became my work. And I was doing that because there was a reason to try to become more rational. I guess because I was so left of field or in the mystical camp, but my thinking was a bit sloppy, which you can find with a lot of people who are on the mystical side of stuff. So, I needed to try to strengthen my thinking by getting the education I’m getting, even though I don’t feel I’m very good at it, but being exposed to the sort of rigor that you are exposed to at ANU, that’s been my practice for a long time.

So, I replaced that being good by doing this, and there was a reason to do it to address an imbalance in the way I think. So, I think I let go of that spiritual practice, but I still have reasons for the choices I’ve made. And they are part of an overall goal in life to, I guess become…I mean, what is our goal in life or what drives us? We try to become as whole, or we try to reach our potential and we make choices about how we do that and what has meaning in our life. And I think what I was doing when I was younger became counterproductive – that way of being good. I don’t think it was bad. I just think I needed to shift gears, get out of that.

Hamilton: I’ve seen it before in others, but also very much for myself, really getting strung out on ideas of being good, goodness, badness, worthy, not worthy, sin, that kind of thing. Seems like a really strong theme, which it seems very extravagant but also seems unremarkable because these are fundamental human concerns and we’re all trying to wrestle with them at different points in different ways.

Shauna: Yeah, I think so. And I don’t want to reduce this to our upbringings and our parents because that’s another kind of reductive…

Hamilton: I know.

Shauna: It’s really tempting to say we had parents that rewarded us for being good or there’s something in the way we were conditioned, but I’m…

Hamilton: Talking to lots of people. No one’s like, oh, my mum did this. My mum’s parenting style about stuff. They talk about traumatic events, but also non-traumatic events. They talk about stuff that happened. Seems at least as important, someone’s upbringing. So, thanks for the encouragement to step away from blaming the mother and other such things.

Shauna: Oh no, I blame my mother totally (laughs).

Hamilton: We’ll have to close in a minute. And we’ve covered a number of different things, but if I can ask you a question that you, we were just saying then we’ve tried to step away from, but can you give yourself a psychoanalytic explanation of this? And if you could, why is it less preferable than some of the other explanations? And I know it probably doesn’t fit for you, but just to record it just so that I have this other account.

Shauna: Look, if you look at trauma, I was adopted as a baby. So, a lot of things about identity as a teenager came up. There are a lot of other things as a teenager that came up around sexuality and gender and the sort of friends I was hanging out with and the problems I had with my parents. I mean, there’s all these traumas going on, and in terms of the parents that raised me, there’s all these undiagnosed personality disorders going on. There are all these things that you could say were contributing factors. And so, when you say I could talk about the kind of parenting that I experienced and how that affected me because of the limitations of my parents, and not saying they didn’t try their best, but there were things about that parenting that were not good and really did contribute to me struggling a lot. And in a way being scapegoated. There’s a dysfunctional family, and as a result, one of the children – me – ends up manifesting these symptoms, but that’s really the result of this dysfunctional unit. So that was definitely a part of it. So, you’re saying, well, why do you need these spiritual explanations of being tested or that there are higher beings or does that replace looking at the traumas that were there when I was growing up and the sort of difficulties in my family unit. And once again, it’s that thing of overdetermination.

We can cite a dysfunctional family and a whole lot of traumas there. We can cite something wrong with the brain and then locate the problem as being in the individual physically. Or then I can take what seems like flights of fancy and say, well, there are these higher beings, and I don’t know why, but for some reason when I entered these worlds, they engaged with me and put me through these tests. And then someone’s saying, well, those tests, is that really reflecting something about what you had to do to be good enough for your parents. You were never good enough for them. And somehow these tests were you trying to be good. They are this child who is just really, really trying to get their parents’ approval, which they can’t get. I don’t have the answers to all of that. I don’t know. The experiences seem very real to me. But yes, there are all these other factors.

But I guess the problem with arguing that trauma is the basis of people’s psychosis is that an awful lot of people experience trauma and they don’t all become psychotic. And then in terms of the content of the psychosis, maybe anyone could experience that. And it’s just kind of random. Whoever actually has the experience.

And see, I guess like you, I want to sit with the experience and make sense of the experience, but there are these other ways of explaining it in psychoanalytic terms or psychodynamic terms or in biomedical terms, and they are causal explanations. But we want to sit with the experience and say, this experience felt real. How can I make sense of it? And if we actually don’t judge the experience, but accept it for what it is, we need to make sense in our own way.

And no one helped me make sense of these when I was younger. I just had to find some way of making meaning and the people writing delusion literature, which I respect, but they will say, you’ve made this meaning because it helps you in your life. It gives you some kind of strength by making meaning out of it the way I have. And there’s a reason for that. But I don’t know. I’m saying that there are these two realities. There’s this scientific physicalist one and there’s this one where there are these conscious beings that care about us and engage with us, and I have this faith that there’s this universe that wants what’s best for us. So, I don’t know if that’s a good explanation.

Hamilton: It’s a very good explanation. I’m so glad you said all of that so succinctly. That was moving actually. I really have similar hopes to you from a personal perspective, but I just want to hear what other people have to say on it. And it does seem there are themes that are emerging. And thanks for being able to reflect on the totality of it and some of your own experiences. And I think time has got away from us.

Shauna: Yeah, sorry. Thank you.

Hamilton: I’m going to stop recording.